Talk to your doctor if you or someone close to you has symptoms of Lewy Body dementia.

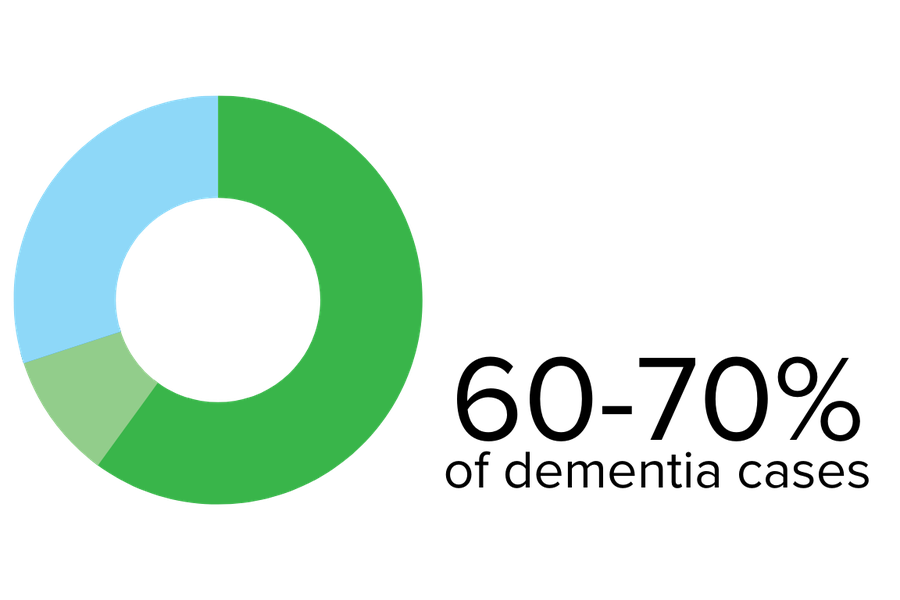

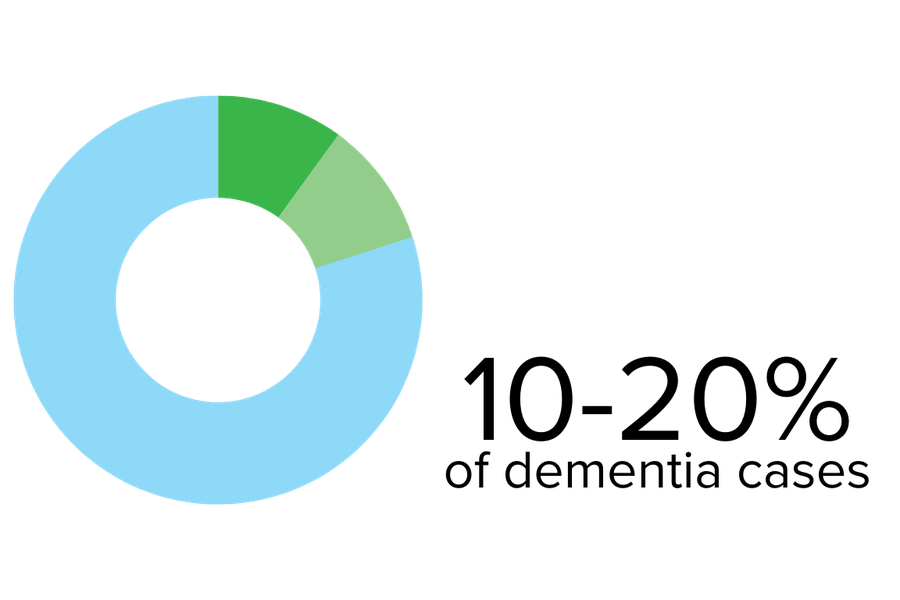

Lewy body dementia is an umbrella term that includes Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies.

Lewy bodies are abnormal collections of proteins in the areas of the brain that control movement, cognition, and behaviour. Your doctor can explain more about these proteins if you or someone close to you is diagnosed. Advanced age is considered the most significant risk factor, with onset typically between 50 and 85, but some cases have been reported much earlier.

Talk to a doctor early.

There are some life-threatening illnesses associated with Lewy Body dementia. An early diagnosis of Lewy Body dementia is critical. Talk to your doctor immediately if you have any of the symptoms mentioned above.

REM sleep behaviour disorder may be an early symptom of Lewy Body dementia. Let your doctor know if you are experiencing any of the symptoms described.