Talk to your doctor if you or someone close to you has symptoms of Young-Onset dementia.

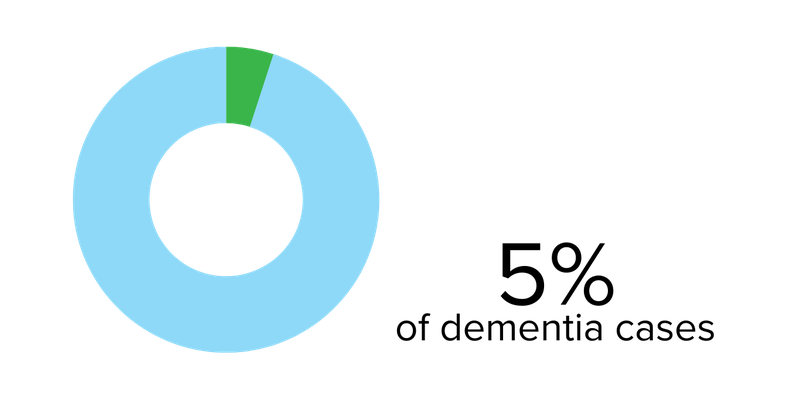

This dementia occurs in people below the age of 65 years.

People diagnosed with young-onset dementia are often in their 40's or 50's. Young-onset dementia is more likely to cause problems with walking, movement, balance, or coordination. However, some people may not have severe health conditions other than dementia.

People with young-onset dementia and their caregivers need support with the following:

- preparing for a new reality with unexpected challenges

- their fears and feelings about the uncertainty of the future

- the stresses of balancing work, family, and caregiving responsibilities

- concerns about financial security

The first signs of young-onset dementia can be like those of late-onset Alzheimer's. The sequence in which signs appear varies from person to person.

What causes young-onset dementia?

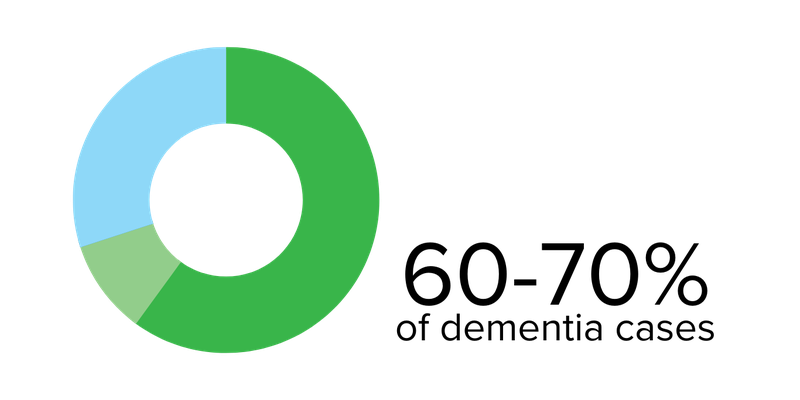

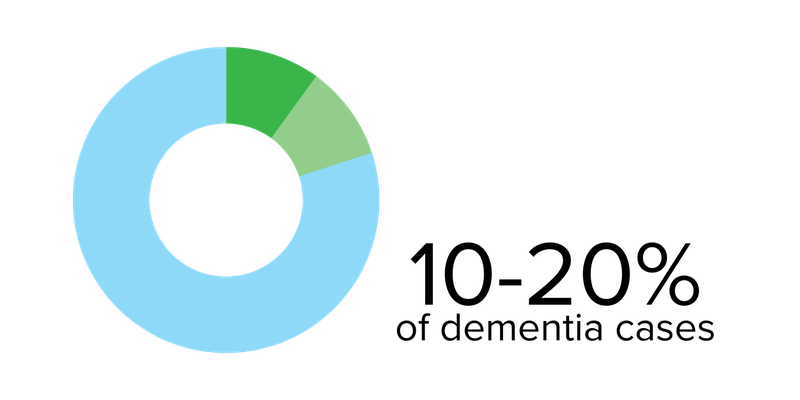

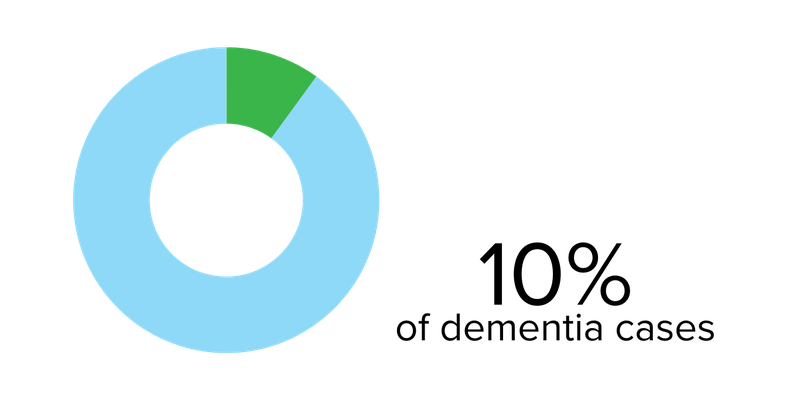

Young-onset dementia may be caused by the same diseases that cause dementia in an older individual. Follow these links to learn about the other types of dementia that may be associated with young-onset dementia:

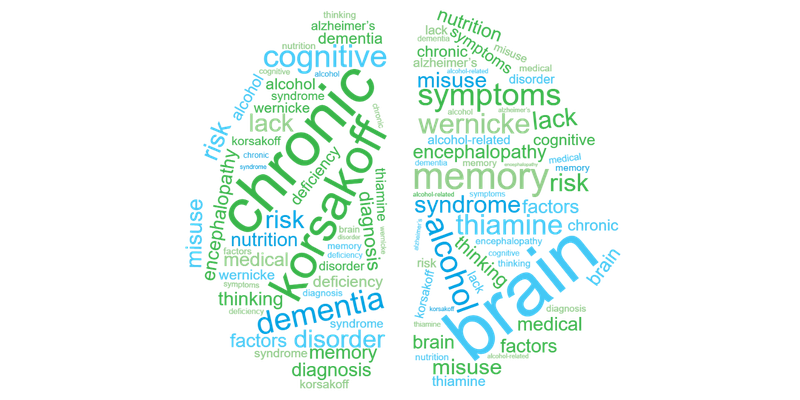

Alcohol-related brain damage

This most often happens to people in their 50s who regularly consume excessive amounts of alcohol. This also includes Korsakoff's Syndrome. The symptoms may be like those of Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia.

Some conditions that occasionally create dementia can be treated if they are diagnosed early, such as vitamin deficiency, thyroid problems, and sleep apnea. Speak to your doctor.

Some rare causes are because of neurological conditions where there is progressive damage to the nervous system. These include Huntington's Disease and Creutzfeldt-Jackob Disease.

Other rare causes include:

- Hormone disorders (like thyroid problems and Addison’s disease)

- Deficient Vitamin B12

- Inflammatory conditions (like Multiple Sclerosis)

- Infections (like HIV, commonly referred to as AIDS)

- Sleep apnea